The greatest of musicians, an epoch-maker, a visionary, Ustad Vilayat Khan was all that and much more. He occupies the pre-eminent place in the world of Hindustani classical music being a legend by virtue of his exceptional musicianship, matchless creativity, dazzling brilliance, superlative perfection, awesomely brilliant techniques and acknowledged mastery over the instrument. Combined with strong base of traditionalism, his own contribution had made him an authority and an icon of Indian Classical Music.

Upholding the unparalleled musical legacy, Ustad Vilayat Khan had musical blue blood in his veins. His grandfather Ustad Imdad Khan was considered as the greatest master of sitar and surbahar among his contemporary musicians and performed throughout the Indian subcontinent. He performed for Queen Victoria during her visit in India. Imdad Khan was the first sitar player ever to come out with a recording. Vilayat Khan’s father Ustad Enayet Khan was India’s most prominent master of sitar and surbahar in his time. Enayet Khan was the pioneering artist who had a great and unrivaled following throughout the country. Both Vilayat Khan’s maternal grandfather (Ustad Bande Hussain Khan) and maternal uncle (Ustad Zinda Hussain Khan) were great vocalists of Shaharanpur.

Vilayat Khan’s prime Gurus (teachers) were his father, paternal uncle Ustad Wahid Khan, maternal grandfather and maternal uncle. He got guidance from his mother Bashiran Begum during his practice sessions. Opinions differ regarding his exact year of birth, some saying 1924, others 1926 or 1928. In the family like Vilayat Khan’s children learn musical idioms in parallel with learning their mother tongue. It was 1934 when he had formal ‘Ganda Bandh’ by his father. Young Vilayat Khan’s first public performance was at All Bengal Music Conference, organized by Bhupen Ghosh of Pathuriaghata, Kolkata in 1936. Rabindranath Tagore, Ustad Faiyaz Khan, Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan, Pt. Omkarnath Thakur, Zamirudddin Khan Sahib among others, were in the audience. He was accompanied on the tabla by Ustad Ahmedjan Thirakwa, the Mount Everest of tabla. Vilayat Khan recorded his first 78 RPM disc at the age of 8. Enayet Khan Sahibs’s untimely demise in 1938 was a turning point in Vilayat Khan’s musical career. This only made him more determined in his passionate quest for his musical brilliance. He had to struggle a lot to establish himself during this period. His musical training continued under strict guidance of his mother, Bande Hussain Khan, Zinda Hussain Khan and Wahid Khan.

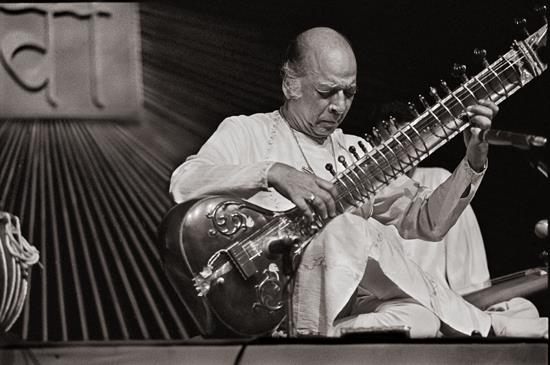

The historic performance by Vilayat Khan at the Vikramaditya Sangeet Parishad, Mumbai made the headline as ‘Electrifying Sitar’ in 1944. The great vocalist Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan also came into lime light at the same event. The audience applauded Vilayat Khan’s performance greatly and he was obliged to play five consecutive encores. The rest of his music career is history. He along with the handful of his contemporary vocalists and instrumentalists contributed to the Indian classical music to a significant extend, which eventually created the most glorious period in the history of Hindustani music.

The contribution of Ustad Vilayat Khan in the evolution of Sitar baaj is outstanding, as well as everlasting, both in terms of classical approach, technical and structural changes of the instrument.

He was the first one among the emerging instrumentalists of his time, who actually expanded the horizons of instrumental music to the highest extent. Though he was gifted with the great treasure of his family music, he was not satisfied with them only. The extraordinary musical creativity insisted him to explore new musical horizons that were untouched and unseen before him.

Creation of ‘Gayaki Ang’ is considered as the very important and lasting contribution of Vilayat Khan in the world of Indian classical music. At the time of ‘talim’, his maternal grandfather and uncle used to demonstrate musical phrases by singing, which helped him to create the revolutionary ‘Gayaki Ang’ on instrument. He has done practice together with his contemporary great vocalists. Gradually he imbibed his style with stylistic nuances of legendary departed vocalists. The prime essences of great vocalists that were adopted by him are mentioned below:

Ustad Faiyaz Khan (Agra) – ‘Sthayi’, ‘Antara’, ‘Halak Taan’, ‘Nom tom Jod’ pattern; Ustad Abdul Karim Khan, Pt. Omkar Nath Thakur – Sur lagane ki tameez (charming application of notes); Ustad Alladiya Khan & Ustad Rajab Ali Khan – ‘Taan’o ki fande aur Bal Panch (‘Taan’pattern).

He had influence of Abdul Wahid Khan Sahib (Kirana), Johra Bai (Agrewali), Mustaq Hussain Khan (Rampur-Sahaswan) along with his contemporaries like Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and Amir Khan. His brother in law Mohammed Khan (father of Rais Khan) had influences on him in his formative years. As a result, Vilayat Khan’s rendition became so lyrical and melodious, it was said that Vilayat Khan’s Sitar virtually sings.

His ‘Alap’ principally follows the ‘Baddhat Vistaar’ following the tradition of Kirana Gharana. Pt. Arvind Parikh rightly describes Vilayat Khan’s ‘Alap’ style as ‘Story telling manner’. The notes are enfolded by petal by petal, according to Raga-Swarup in the full length ‘Alap’. Developing a greater range in the ‘meend’ allowed playing longer pieces in the Khayal and ‘Thumri’ styles. His ‘Alap’ was clearly built and systemized with ‘Sthayi’, ‘Antara’, ‘Sanchari’ and ‘Abhog’, the principal parts of Dhrupad ang ‘Alapchari’, though his rendition style was influenced by post-dhrupad era music. Sometimes his ‘Taan’s in different ‘Prakars’ (variations) and in different ‘Angs’ in his heydays were seemed to be a challenge not only for the instrumentalists but also for the vocalists. Starting from top grade artists to today’s young generation musicians (including vocalists) keep Vilayat Khan’s ‘Taan’s as their model. He also introduced multiple complicated playing techniques on sitar, which were never used before.

Though Gayaki style dominates his repertory, there is a substantial amount of instrumental material in his playing, like ‘jamjama’, ‘gamak’, ‘lahak’, ‘lapet’, ‘khatka’, ‘jhatka’, ‘krintan’, ‘murki’, ‘gitkiri’, ‘chhand’, ‘laykari’. His repertory consisted of Imdad Khan’s ‘tantra ang baaj’, ‘gat toda’, Enayat Khan’s ‘Sapat Taan’, ‘Tihai’, ‘peshkara’, ‘tobba’, ‘chakkardar’, ‘kaida’, ‘thaduni’, strong and intricate ‘Bol’ pattern etc. As a result of this, he was successful to build the revolutionary Sitar Baaj, which is now universally accepted as Vilayatkhani Baaj. The Silsila-war, sequential expansion of Raag, Badhat that he had in his music, was the result of tremendous talim, vigorous riyaz and superior aesthetic sense. The level of ‘Taiyaari’ he achieved in his heydays is still unmatched. The lightening speed, perfect crystal clear execution, sequential beauty of the contents (silsila-war) and delightful executions made him the idol among his followers. After his father Ustad Enayat Khan, he was the pioneer among the instrumentalists to bring the romantic approach in classical music. He has introduced interesting facets to his musical content without any damage to the traditionalism.

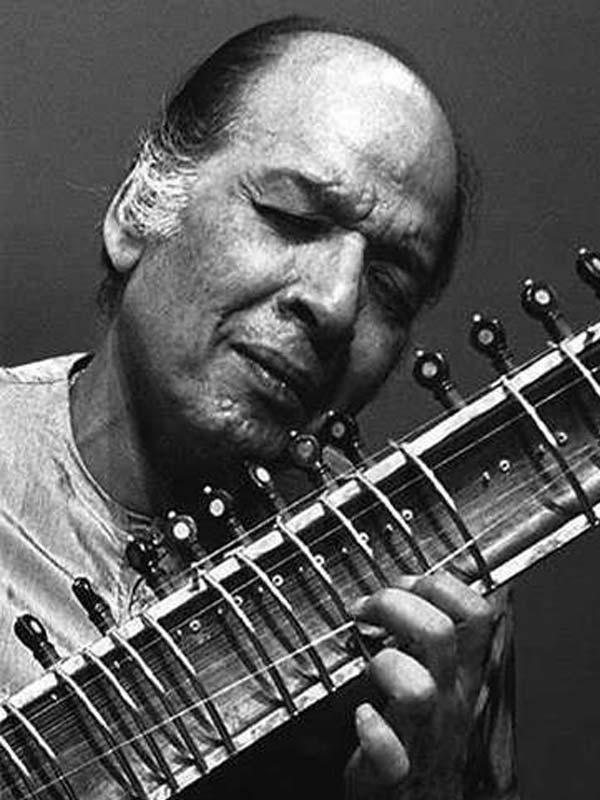

Some musicians raised their eyebrows on calling Vilayat Khan’s style as ‘Gayaki Ang’ saying that ‘Gayaki Ang’ on instrument is nothing new, as vocal music is mother of all kind of instrumental music. The fact is: unlike a bowing instrument like Sarangi, where long duration notes can be achieved by bowing motion produced by the player, sitar is plucking instrument where each note produced by a stroke has limited duration. Vilayat Khan introduced a completely new left hand technique by which continuity of a note with much duration was achieved. This brought the unusual lyrical fluidity in his music. What Vilayat Khan has done is significantly different from others. He introduced very difficult and highly intricate ‘khayal-ang murkis’, dynamism and flow of sarangi, ‘meend’ of long range as used in vocal music, ‘Taan’ patterns which follow the vocal idioms. Even his rendition of ‘Thumri’ can be taken as the proof why his style is rightly called ‘Gayaki Ang’. Though his father introduced small ‘khayal ang murkis’ and vocal model of ‘Taan’ patterns, Vilayat khan had done the full-fledged introduction of ‘Gayaki Ang’ in all stages of performance.

The quality of Sitar-tone was not very advanced before, compared to the new scientific microphone systems. Due to light and very sharp jawari, their Sitar tone had lesser depth and the sound of melodic strings could not be sustained long. Vilayat Khan had changed the structure of sitar in such a way, that all the shortcomings of the instrument were overcome. The tricky use of all the strings and modified use of jawari (Round Jawari) made it possible to sustain the duration of a stroke which resulted the continuity of the melody. He has been widely acclaimed as the architect of the modern sitar

Vilayat Khan closely worked with great instrument makers including Kanai Lal Das (Kolkata), Hiren Roy (Kolkata), and Bhishan Das Rikhi Ram (Delhi) to redesign the instrument. He removed the lower pitched extra ‘Jod’ string and brass-Pancham string and replaced them with one steel Gandhar string. He also slightly raised the height of the bridge (to make a larger gap between strings and the frets), strengthened the Tar Gahan (to withstand greater range of pulling string with left hand), and introduced a thicker Tabli (to withstand tremendous pressure of the right hand stroke). Ustad Vilayat Khan was not only a traditionalist, but also an innovator. That’s why the words ‘Orthodox’ and ‘Revolutionary’ are appropriately used to describe his rare genius. He was always much ahead of his time in terms of sophisticated presentation, superior musical ideas, and colorful imaginative presentation. In his performance career of almost eight decades, he made a class of his own listeners to whom he was virtual god in music. His ‘Thumri’ could leave the listeners in the memory lanes full of nostalgic melancholy. After each and every concert, listeners were charmed by ‘Vilayat Khani mizaj’, even not being ready to listen to the next artists of the concert. Sri Deepak Raja says: ‘His renditions … acquired a haunting quality that often rendered his admirers sleepless after a concert. This nostalgia triggered off by his renditions in the Ustad’s ‘Thumri’ style renditions’. His vivid imagination made his ‘Thumri’ pieces so colorful. As widely believed, Vilayat Khan’s musical imagination was not dependent only upon vocal music. He has adopted musical ideas from each and every source which had appealed him, that may be a female street beggar’s song, chimes of London’s Big Ben or voice of a cuckoo. His aristocratic and refined presentation of Raga music, heart blending presentation of semi classical music, even folk music concurred the hearts of millions,making him a true legend.

Though Vilayat Khan was well known to perform mostly on common ragas, he had vast in-depth vision on rarely heard ragas including ‘jod’ and ‘achhop’ ragas. He preferred to perform rare ragas only occasionally, that also for learned audience. In most part of his career, he performed on matured ragas and his attempt was gradually exploring the depth of the raga and capturing the raga from different angles. He is said to be first traditional interpreter of grand matured ragas like Yaman, Bihag, Puria, Shree, Ahir Bhairo, Todi, Malkauns, Darbari, to name a few.

Though he received intense ‘talim’ from his family members, his quest for more and more knowledge on Raagdari forced him to collect Raga-ness and different vocal compositions of the rare and ‘Jod’ ragas from his peer vocalists. That’s why he is sometimes referred as ‘self-taught’ musician.

Critics say, Vilayat Khan’s music sometimes has deviated from correct raga grammar. Fact is: though he occasionally used to take ‘Poetic Liberty’ to implement ‘Avirbhav-Tirobhav’ kind of ‘alankars’, his treatment could never be considered as ‘waywardly’. He never bothered to be consistent to maintain the unidirectional motion of the Raag. In different concerts, he always has done experiment to explore the ragas in greater and greater depth and look the raga from different angles. So, his each single recital used to create different impressions in the listener’s mind, even though he might have played the same raga in multiple concerts.

Once in a concert he applied comparatively a greater proportion of ‘Dhaivat’ in Bihag, which was hallmark of Lukhnow Gharana. In another concert, he added a ‘Kan’ of ‘Tivra Madhyam’ in Bilas Khani Todi (reflection of this can be found in Ustad’s rendition of the same raga on surbahar) which created controversy among the musicians. According to eminent musicologists, while going to Pancham, this kind of Kan of Tivra Madhyam was used in all prakars of Todi, in Tansen’s gharana. Very consciously he imbibed the old treasures of Raag-roop.

He mostly performed on Teen-Taal, occasionally performed on Vilambit / Drut Ek-Taal and rarely on Jhaaptaal and Roopak. His ‘Thumri’ compositions were mostly based on Dadra, Kaharwa, Jat, Sitar-khani theka. He composed many outstanding compositions on Jhap Taal, Roopak, Ektaal, Jhampak (11 Matra), 13 matra on different ragas. His composition on Hamsadhwani on drut ektaal, Desh on Jhap Taal, Bageshree on Madhya Laya ektaal and Bhairavi on Madhya laya Roopak (‘Tum ho Jagat ke Data’ – which he taught to great vocalist Pt. Ulhas Kashalkar) needs special mention here. Perhaps he never performed on so called ‘and half’ taals, which don’t even have the stature to be called as ‘Taal’. The probable cause for the same may be those do not have chrematistic match with his musical temperament.

He had a huge collection of authentic vocal ‘bandishes’ (compositions). In his concerts, he used to demonstrate some special movements of Raga or a composition by singing. Many celebrated vocalists including Begum Akhtar, Ulhas Kashalkar formally learnt from him. He composed many vocal compositions with the pen name ‘Nath-Piya’.

Ustad Vilayat Khan performed some of the immortal duet concerts with Ustad Bismillah Khan (shehnai), Ustad Ali Akbar Khan (sarod), Ustad Imrat Khan (surbahar) among others. His LP recordings with Ustad Imrat Khan are treated as the finest recordings on instrumental music. He was not very keen to allow his audience to record his live music. However, music lovers across the globe still have fanatic affinity for collecting, preserving and listening to his recordings. There are more than 100 published recordings and more than 1000 hours of his concert recordings, which are treated as treasures by music lovers, music students and connoisseurs alike. These are most actively exchanged among connoisseurs across the globe.

Ustad Vilayat Khan had very little but distinctive presence as music director in films. He composed music for Madhosh -1951 (background music as Khan Saheb Vilayat Khan), Jalsaghar (The Music Room – 1958), The Delhi Way (1964), The Guru (1969), Kadambari (1976), Jal-Jangal , Ulka (Bengali Film), Notun Foshol (Bengali) -new theatres. However, Jalsaghar is the only film by great Satyajit Ray which won Award for music. This film grabbed Silver Medal for Music in Moscow Film Festival, 1959. He was also awarded as the best composer for Jalsaghar.

Ustad Vilayat Khan had innumerable disciples including Pt. Arvind Parikh, Pt. Kashinath Mukherjee, Smt. Kalyani Roy, Pt. Giriraj among others. His brother Ustad Imrat Khan and nephew Ustad Rais Khan are considered as the top notch sitarists of all time. His sons, nephews (especially Shahid Parvez Khan, Nishat Khan, Shujaat Khan, Irshad Khan) are the most prominent names in the Instrumental music today. However, the biggest contribution of Ustad Vilayat Khan in the field of sitar (instrumental music in general) is, there is virtually not a single instrumentalist today who have not been influenced by him. His music had influenced his contemporary doyens of other musical lineages including Pt. Nikhil Banerjee, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan. Great musicians of the next generation (especially Budhaditya Mukherjee) are also highly influenced by him. His perfect and smart posture with the instrument, perfect position of right and left hand on instrument, redefined technique of movement of hands on instrument, variation of angle of stroke are considered to be ideal by his followers. Today, number of followers of Ustad Vilayat Khan exceeds the total number of other Gharana sitar-players. Teed Rockwell (the musician and musicologist) rightly says: ‘Anyone who plays the sitar, or any stringed Indian instrument today, owes him (Ustad Vilayat Khan) an incalculable debt. His vision of how the instrument should be played and built has become the standard by which all sitar players are now judged.’

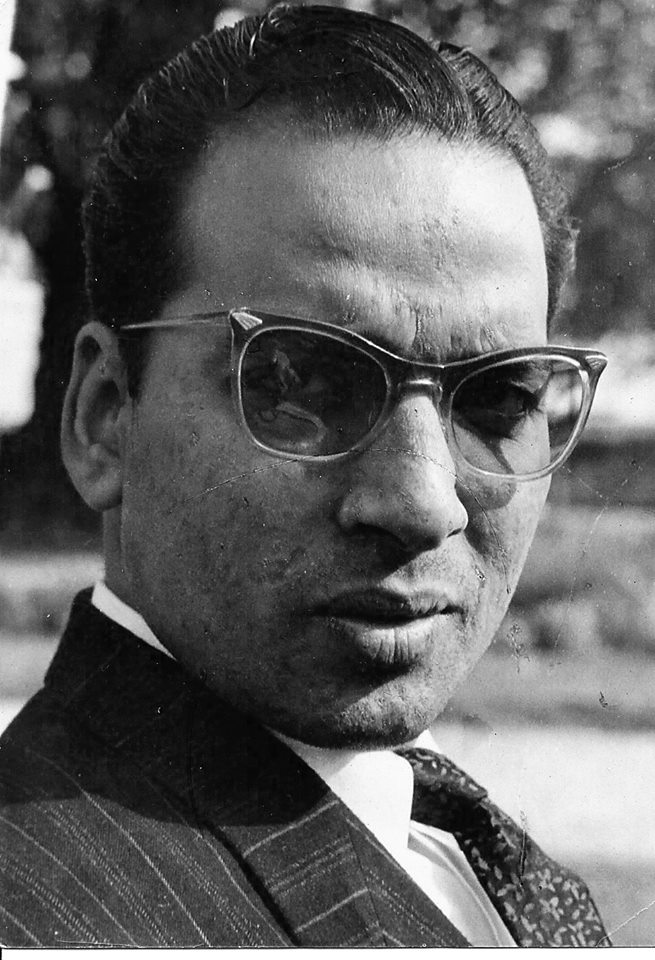

Ustad Vilayat Khan was one of the most charismatic musicians of India, like Ustad Faiyaz Khan and Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. His aristocratic stage appearance was so unique, that used to reflect his royal personality. He used to take a total control on his audience by his gracious presence, royal look, and artistic choice of dresses, combined with behavioral etiquette on stage. He had a great collection of perfumes, sun-glasses, shawls and guns. He was a master ballroom dancer, billiard player, swimmer and horse rider. He enjoyed driving high-end performance cars that he owned. On his performance, the King of Afganistan was so pleased; he presented a Mercedes to him.

Ustad Vilayat Khan was a man of principles and lived his life in his own terms. He always considered the musician as the divine connection between God and the audience. Hence he expected his audience to accept music with a spirit of reverence. This mind-set neither allowed him to twist his musical ideas to gain any kind of cheap popularity nor tolerated anyone to humiliate his musicianship. He was the long term critic of the transparency in the gradation system of All India Radio. He rejected the highest civilian awards offered by the Government of India for thrice on the grounds that the committee was incompetent to judge musicality and artistry. He was the only sitarist to receive the title “Bharat Sitar Samrat” (Emperor of Sitar) by the Artistes Association of India and “Aftab-E-Sitar” (Sun of the Sitar) from President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed.

Considering Ustad Vilayat Khan’s overall contribution in the stylistic evolution of sitar, his creation of the new vocabulary of instrumental music, the impression he left on the next generation musicians, and the love and respect with which the music fraternity has embraced him– it can be said that he was not only one of the greatest instrumentalists ever, but also ranks amongst the all-time greats of Hindustani music.

Written by Ramprapanna Bhattacharya